Disabilities of Arm Shoulder and Hand (Dash) Review

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Responsiveness and minimal important change of the Norwegian version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (Nuance) in patients with subacromial pain syndrome

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume xviii, Article number:248 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Mitt questionnaire (DASH) is a valid and reliable patient-reported outcome measure (PROM). Information technology was designed to mensurate physical disability and symptoms in patients with musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity, and is one of the most commonly used PROMs for patients with shoulder pain. The aim of this study was to examine responsiveness, the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC) of the Dash, in line with international (COSMIN) recommendations.

Methods

The study sample consisted of 50 patients with subacromial pain syndrome, undergoing concrete therapy for 3–4 months. Responsiveness to change was examined past calculating expanse under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) and testing a priori-formulated hypothesis regarding correlations with changes in other instruments that measuring the aforementioned construct. The SDC was calculated using a test re-test protocol, and the MIC was calculated by the anchor-based MIC distribution. MIC values for patients with low and high baseline scores were also calculated.

Results

Nuance appeared to exist responsive, as it was able to distinguish patients who reported to exist improved from those unchanged (AUC 0.77). All of the hypotheses were accepted. The SDC was eleven.8, and the MIC was four.4.

Conclusion

This study shows that the Norwegian version of the Nuance has proficient responsiveness to alter and may thus be recommended to measure upshot in patients with shoulder pain in Norway.

Background

Shoulder hurting is common in the general population with a reported 1-year prevalence of 5–47% [ane]. Subacromial pain syndrome is the most mutual diagnosis for patients with shoulder pain [2]. Numerous patient-reported upshot measures (PROMs) are available for the evaluation of shoulder disorders [iii]. PROMs accept get standard instruments in intervention studies, and are increasingly being used in clinical practice to capture patients' cocky-reported part, disability and health [four]. The use of PROMs in clinical practice can atomic number 82 to improved patient-clinician communication and enhance patient intendance and outcomes [five]. It is essential that PROMs demonstrate acceptable psychometric properties [6]. To obtain consensus of how measurement properties are defined and tested, an international Delphi process has been carried out to develop methodological guidelines, called the COnsensus-based Standards for the development of Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) [7, 8]. A prerequisite for a PROM to be used for evaluation in both clinical practice and research, is the instrument's responsiveness [9]. Responsiveness is defined as "the ability of an instrument to detect change over time in the construct to be measured", and is considered an aspect of validity [7]. To interpret change scores of a PROM 2 benchmarks are required: the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC), which the COSMIN group defines respectively as "the smallest change that can be detected by the instrument, beyond measurement fault" and "the smallest change in the construct to be measured which patients perceive as important" [ix].

The DASH is a region specific PROM, and is according to Roy et al. [x] the most usually used questionnaire for assessing shoulder function. Information technology was developed to measure physical disability and symptoms of single or multiple disorders in the upper limb region [11], and has been translated into several languages including Norwegian [12]. The DASH has shown acceptable reliability, validity and responsiveness across a number of shoulder pathologies [10, 13].

However, according to the COSMIN panel inadequate methods for examining responsiveness and MIC take been practical, such as consequence size (ES), standardized response mean (SRM) and distribution-based approaches [14]. The COSMIN panel claims that these methods measures the magnitude of an effect, and not the instruments power to detect change over time or the importance of the change [7, 9]. Roy et al. [10] pointed out the need to behave more studies regarding the estimation of MIC in shoulder inability scales. Since the responsiveness and MIC of a PROM may vary past population and context [15], it is important to examine these measurement backdrop in different samples of patients.

To our knowledge, responsiveness of the DASH has not previously been examined in line with the COSMIN recommendations. Hence, the purpose of this written report was to assess responsiveness, and to determine and compare the SDC and MIC of the Norwegian version of the questionnaire following these guidelines.

Methods

Study participants and process

This clinimetric study included patients with subacromial pain syndrome (SPS). The patients were recruited from an outpatient clinic for physical therapy and rehabilitation at X, from December 2007 to October 2010. The patients were referred to "usual physical therapy" in primary health care, partly financed by the public health insurance service. The inclusion criteria was a diagnosis of SPS given by an orthopaedic surgeon based on clinical findings and symptoms, including inductive-lateral shoulder pain worsening during elevation of the arm and overhead activities, positive isometric abduction and positive impingement sign [sixteen]. Exclusion criteria were systematic disease or generalized hurting, cardiac illness, symptoms of cervical spine illness or surgery in the affected shoulder within the last vi months. Patients were as well excluded if they were unable to read or speak Norwegian fluently. Ethical approval was obtained by the Norwegian Regional Committee for Ideals, and all the participants signed a written consent form.

The assessments for the present written report were completed at three different fourth dimension-points: T1 (baseline), T2 (1–2 weeks after baseline) and T3 (3–iv months follow-upwardly). At T1 they completed the Nuance, Shoulder Pain and Disability Alphabetize (SPADI), Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36), Numeric Pain Rating Calibration (NPRS), and provided demographic information. Active range of motion (AROM) (shoulder abduction, flexion, and internal and external rotation) was measured with a goniometer past a physiotherapist. At T2, the patients only filled out the Nuance and SPADI. After completed handling (T3) they filled out Nuance, SPADI, SF-36, and NPRS, and AROM was measured. Perceived recovery was reported past the patients on a 3-level ordinal calibration. Mean DASH scores of T1 and T2 were calculated as a basis for measuring change.

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (DASH)

The Nuance consists of a 30-item calibration that contains 21 physical function items, five symptom items and four social part items. Each item has 5 response options apropos the patient's symptom severity and role of the upper extremity in activity during the previous week. The scores range from 0 to 100, where 100 reflects the most severe inability. The Dash was considered incomplete if more than than ten% (missing rule) of the items scores were missing. Missing items were imputed as the average of the remaining items [17]. A previous study based on the same sample of patients demonstrated adequate exam-retest reliability, internal consistency and construct validity of the Norwegian version of the DASH [18].

Other cess tools

The Shoulder Hurting and Inability Index (SPADI) measures shoulder pain and disability, and contains xiii items in ii domains: pain (v items) and disability (8 items). The full score ranges from 0 to 100, lower scores indicating less pain and disability [19]. According to systematic reviews, the SPADI has demonstrated high reliability [10, 20] and satisfactory validity in large groups of patients with shoulder hurting [21], but its validity and reliability has been questioned in a recent review [22]. The Norwegian version of SPADI used in this study has shown adequate validity and reliability [23].

The Short Course 36 Health Survey (SF-36) measures wellness in viii domains: physical performance (PF), office-physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), perception of general wellness (GH), energy and vitality (VT), social operation (SF), office limitation due to emotional problems (RE), and mental wellness (MH). The results range from the worst outcome (0) to the best outcome (100). The SF-36 was used as a generic measure of health, recommended to supplement status-specific measures in shoulder patients [24]. The scoring was carried out following the published guidelines [25]. The Norwegian version of SF-36 has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties [26].

Numeric Pain Rating Calibration (NPRS) captures the patient'southward level of hurting. It is an xi-point scale that is anchored on the left with "no pain", and on the correct with "worst hurting possible". The patients were asked to rate their current pain within the last 24 h. NPRS has shown practiced reliability and responsiveness, with reported MIC values varying from 1.1 to two.17 in patients with shoulder pain [27, 28].

Perceived recovery. At the iii–four months' follow-upwardly (T3) the patients were asked to rate on a three-level ordinal scale whether their condition had improved, was unchanged or had deteriorated since baseline. The use of a change scale is common, while designs and the number of scoring alternatives may vary. In a recent review alter scales were shown to be reliable and responsive [29], and splendid test-retest reliability was demonstrated in patients with musculoskeletal disorders [30], although validity has been questioned [31, 32].

Assessment of responsiveness

Both benchmark and construct approaches were used to examine responsiveness [ix]. As a criterion arroyo, the perceived recovery after handling was used as an ballast (aureate standard) for important changes in Dash scores. A dichotomous variable (the 'improved' versus 'unchanged') from the measure of change (perceived recovery) was used to examine the discriminate ability of alter scores from the questionnaires, using the receiver operating curves (ROC) method. The expanse under the ROC curve (AUC) was used as an indicator of responsiveness. AUC is a measure of the musical instrument's ability to discriminate between 2 groups according to an external golden standard (here: perceived recovery). For sufficient responsiveness, an AUC over 0.70 is recommended [nine].

The construct approach includes a priori hypotheses of expected associations between scores of DASH and other cess tools that mensurate more or less the same construct (NPRS, SPADI, SF-36 and AROM). The force of the positive correlation coefficients were interpreted co-ordinate to Munro [33]: little, if whatsoever (.00–.25), low (.26–.49), moderate (.50–0.69), loftier (.seventy–0.89) and very high correlation (.90–1.00). Negative correlations were interpreted in a similar manner. Nosotros used criteria described by de Boer et al. [34], which rates responsiveness as high if less than 25% of the hypotheses are refuted, moderate if 25–l% are refuted and poor if more than than 50% are refuted. The hypotheses tested are explained in particular and presented in Table 1.

Measurement error by Smallest Detectable Change (SDC)

The patients did not receive any handling between T1 and T2. These two measurement points were used to determine measurement error. Measurement mistake can be expressed by the standard error of measurement (SEM) and the SDC. The COSMIN-group defines SEM equally the standard deviation (SD) around a unmarried measurement [9], and it was calculated as the square root of the inside-subject area full variance of an ANOVA analysis [35]. The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was computed using a ii-way mixed furnishings model for total agreement. The SDC was calculated every bit 1.96 × √2 × SEM. If change is above this value in individual patients 1 can exist 95% confident that information technology is not caused past measurement fault [36].

Minimal Important Change (MIC)

To explore interpretability of alter scores, the SDC was compared to the MIC. To distinguish clinically of import change from measurement mistake, the MIC should be greater than the SDC. The MIC was determined past using visual anchor-based MIC distribution based on the ROC method [37]. The perceived recovery was used as an ballast, dichotomized as 'improved' and 'unchanged'. The subgroup 'deteriorated' was not included in the ROC bend assay. The sensitivity and i-specificity values from the 'improved' and 'unchanged' grouping were plotted on the y- and x-axis to distinguish the two groups. To define the MIC for the DASH a ROC cut-off point was detected, by finding the maximized value of both sensitivity and 1-specificity [37]. The anchor was considered acceptable if a minimum correlation of 0.v was found between the change scores of the DASH and the anchor [38].

In recent studies the MIC of PROMs has been found to vary depending on the baseline scores [39, 40], and MIC was therefore also calculated for subgroups depending on the median of the baseline scores.

Data analysis

The information was assumed to be ordinarily distributed if in that location was no or minimal departure between the hateful and median value, confirmed by histograms, by Q-Q plot and by the Shapiro-Wilk exam. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were used as appropriate depending on fulfilment of normality criteria. Flooring and ceiling furnishings were considered to be present if the lowest or highest possible score was achieved by more than xv% of the patients [6]. The analysis was performed using the software IBM SPSS version 22 for Mac.

Results

Ninety-four patients met the inclusion criteria, while 29 (31.0%) were unwilling or unable to participate, and two were excluded because of generalized pain. Of the 63 subjects, 13 dropped out before follow-upward assessment later on handling (between baseline test and 3–4 months follow-up). The final study population consisted of 22 women and 28 men, with a mean age of 54.4 years (Table ii). The mean handling length was fifteen.viii weeks. Table 3 presents the patient characteristic co-ordinate to the perceived recovery in question.

At baseline, two of the DASH items (0.13%) were identified as missing. Five items were missing (0.33%) at T3. All of the completed DASH questionnaires had at least 27 of the thirty items answered (missing rule), and the missing items were imputed as the average of the remaining items.

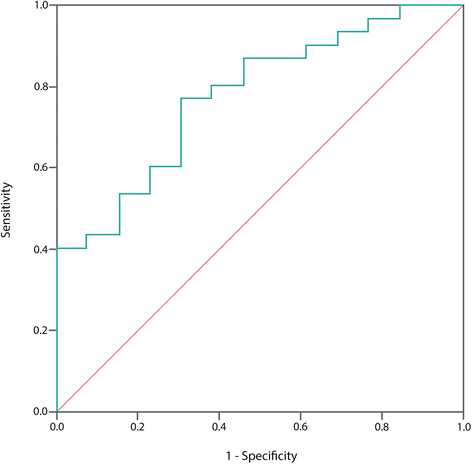

Responsiveness

Figure one presents the ROC curves generated for the DASH. Based on the anchor (perceived recovery), a total of 30 patients reported "improvement" and thirteen "unchanged" (Table 2). The AUC of the DASH was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.63, 0.92).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the change scores of Dash

Table 4 displays correlations coefficients between change scores for the instruments. All hypotheses regarding the Nuance were confirmed, and are presented in Tabular array one.

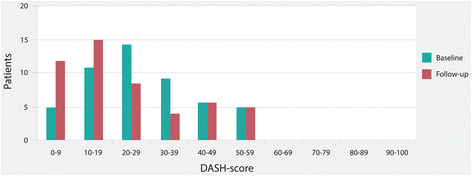

No floor or ceiling effects were observed for baseline or follow-upwardly scores. The score distribution of the DASH is presented in Fig. ii.

Score distribution of the DASH before and after the concrete therapy. College values indicate greater disability

Smallest detectable alter

The mean fourth dimension period between T1 and T2 was vii.4 days (SD, ii.ane). The ICC of the DASH was plant to be 0.91. The SEM was 4.3, and the SDC was institute to exist 11.8.

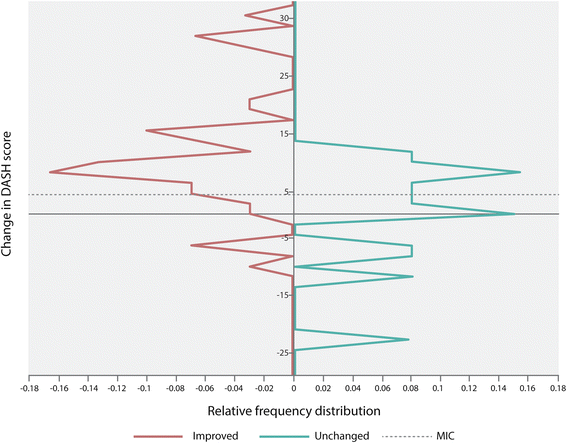

Minimal important alter

Patients who reported deterioration on the perceived recovery (anchor) were excluded from the calculation of MIC. The anchor was considered appropriate since the correlation of both instruments with the anchor was higher than 0.5 (Tabular array iv).

The MIC for the total change scores of DASH was 4.4, with a sensitivity of 0.77 and specificity of 0.69 (Table five). Figure 3 illustrates the ballast-based distribution of the modify scores for the improved and unchanged group, and the MIC value. Using the MIC as a cut-off point, 23.4% of the patients who were "improved" co-ordinate to the anchor, had a lower modify score and were considered false negatives. 30.eight% of the patients, who were "unchanged" according to the anchor, had a higher alter score and were considered false positives.

Anchor-based MIC distribution of the Dash with indication of the ROC cutting-off point, after dichotomizing the patients in groups of improved and unchanged. MIC 4.4. Sensitivity at this bespeak was 0.77 and specificity was 0.69

MIC values for low and loftier baseline scores was respectively 4.iv and vii.7. The median Nuance score was 26.4. Twenty-ii patients (15 improved, 7 unchanged) had low Nuance baseline scores (i.e. Dash ≤26.4). Twenty-1 patients (15 improved, 6 unchanged) had high Dash baseline scores (DASH > 26.iv). The MIC information are presented in Table five.

Discussion

The DASH is often used in research and clinical do to evaluate disability and the effect of interventions for shoulder disorders. Therefore, it is important to evaluate its ability to capture change, and especially the smallest change score that patients perceive every bit important.

The study of responsiveness was conducted following all requirements of the COSMIN-checklist [41]: (1) Reporting the percentage of missing items, (ii) describing how missing items were handled, (3) appropriate sample size. The total sample size included in the analysis, was within the range described as good (due north = fifty–99), except for the subgroup assay and the calculation of the MIC which was poor (n < 30). (4) A longitudinal pattern with three measurements was used, (five) the time interval was stated, (6) the intervention was described, and (seven) the proportion of patients that inverse (i.e. improved, unchanged and deteriorated) was described. Regarding the hypotheses testing, (8) the hypotheses were formulated a priori, (ix, 10) the expected direction and magnitude of correlations of the change scores were defined, (11, 12) the comparator instruments and its measurement properties were described. (13, fourteen, 16) The pattern, method and statistics are considered advisable, (15) the criterion for modify (anchor) can exist considered to be a reasonable gold standard co-ordinate to its correlation with the DASH (>0.fifty), (17) both correlation between the alter scores and ROC curve were calculated, and (18) sensitivity and specificity for the patients who were 'improved' and 'unchanged' was adamant.

For evaluating the responsiveness, both a criterion and a construct approach was conducted according to the COSMIN recommendations [9]. Using the criterion approach, this study found show for skilful responsiveness of DASH (AUC = 0.77, CI: 0.63, 0.92). This indicates that the questionnaire was able to distinguish patients who reported to take improved, from those who remained unchanged. The AUC-value found in the nowadays written report is similar to the findings reported in contempo studies. In patients with a variety of shoulder disorders, Lundquist et al. [42] constitute an AUC of 0.76 (0.62–0.90). Michener et al. [43] found the AUC to be 0.79 (0.69–0.89) in patients with shoulder impingement. Similar to our findings, no flooring or ceiling effect was reported in these studies, or in studies that included patients with upper-limb disorders [44, 45].

Co-ordinate to the construct approach, a total of vi hypotheses were a priori formulated regarding the relationships between changes on the DASH and changes on related measures. None of the hypotheses were refuted. DASH showed little to moderate correlation with impairment measures, every bit is consequent with findings in other studies [46, 47].

We institute a MIC value of iv.4 for the total DASH data. This implies that a change of 5 on the scale is probable to be considered important past individual patients. However, measurement error by SDC was found to be 11.8 which is a larger value than all calculated MIC values. This means that individual patients may considered a MIC value to be an of import change. However, as information technology cannot be distinguished from measurement fault it is not statistically significant [48]. Measurement error has to be taken into consideration when interpreting change scores. We should both be confident that the change in Nuance is not just due to measurement fault and that it is sufficiently high to be important to private patients. Hence, a modify value must be over eleven.8 for the DASH to be considered as an important alter. In the present study 11 patients had a change value above 11.8, although 30 patients were considered improved according to the anchor.

Additionally, we found a higher MIC (7.7) for the patients with high baseline scores (Table 5). This supports previous findings that patients with higher baseline scores needs greater changes to be considered as important [37, 40]. MIC can also exist expressed as percentage of baseline values [40]. When calculating the MIC values in our study as percentage, the MIC for the total Nuance is fifteen.8% (4.4 of 27.ix), and for the subgroups with depression and high baseline scores, 25.9% (4.iv of 17) and 19.6% (7.seven of 39.2), respectively.

The SDC value establish in our study is comparable with SDC values reported by others [36, 49, fifty]. The MIC value (4.4) in the present study is, however, much lower as compared to results establish in the literature. Gummesson et al. [51] found a MIC of ten and van Kampen et al. [36] a MIC of 12.4. Beaton et al. [49] studied heterogeneous shoulder patients and compared dissimilar approaches for determine the MIC. Their results ranged from 3.nine to 15. These differing findings indicate how dependent the MIC is on the ballast. The anchor used in this written report was a perceived recovery recorded on a iii-level ordinal scale, similar to what was used in a recent study [47] on responsiveness of the DASH. Using a 7- or 15-point Likert calibration could take been better suited for this report, resulting in a more refined dichotomising between the subgroups. Nevertheless, such anchors have been criticized for not beingness capable of correlating functional change beyond varying lengths of fourth dimension [52]. The anchor used in this present study tin be questioned due to the large overlap between the distributions of the improved and unchanged grouping of patients illustrated in Fig. three according to the MIC value. However, in this written report the anchor correlated above 0.5 with the change score of the Dash, and is then proposed to exist a valid anchor co-ordinate to a recent study [twoscore]. Since in that location is no clear agreement of which method is the best to examine MIC, other approaches could have resulted in unlike MIC values. In addition, both the ballast-based approach and the COSMIN-grouping'south definitions of MIC and SDC used in this report, leads to a clear distinction between these two concepts [9, 53].

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first study to explicitly follow the COSMIN panel recommendation regarding examination of responsiveness of the Dash. Nevertheless, there are some limitations as to how the findings should exist interpreted. First, the COSMIN-checklist was developed to improve the selection of measurement instruments and how to evaluate these measurement backdrop. Nevertheless, the checklist has non still been tested for its reliability, and co-ordinate to the authors it needs further refinement [41]. 2d, the total sample size of this study is moderate (n = l). Although it is within the COSMIN recommendation for exam of responsiveness, the sample size of the unchanged subgroup (due north = 13) used for the analyses was minor. 3rd, an ordinal calibration with more scoring options might have been preferred.

Conclusions

In determination, the Norwegian version of the Nuance was found to be satisfactory responsive when applied on patients with subacromial pain. Based on the SDC and MIC, a change value on the Nuance must be above 11.8 to be considered equally an important change that is non due to measurement mistake.

Abbreviations

- AROM:

-

Active range of motion

- AUC:

-

Surface area under the ROC curve

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the choice of wellness Measurement Instruments

- DASH:

-

The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and manus questionnaire

- MIC:

-

Minimal important change

- NPRS:

-

Numeric pain rating scale

- PROM:

-

Patient reported outcome measure

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating feature

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDC:

-

Smallest detectable change

- SEM:

-

Standard mistake of measurement

- SF-36:

-

Brusque Form 36 Health Survey

- SPADI:

-

Shoulder pain and inability index

- SPS:

-

Subacromial pain syndrome

References

-

Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJM, Burdorf A, Verhagen AP, Miedema HS, et al. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder hurting in the full general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:73–81.

-

Michener LA, Walsworth MK, Burnet EN. Effectiveness of rehabilitation for patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review. J Mitt Ther. 2004;17:152–64.

-

Fayad F, Mace Y, Lefevre-Colau MM. Shoulder inability questionnaires: a systematic review. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2005;48:298–306.

-

Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, Elliott TE, Greenhalgh J, Halyard MY, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes cess in clinical exercise: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1305–14.

-

Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, Guyatt G, Ferrans CE, Halyard MY, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179–93.

-

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;lx:34–42.

-

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–45.

-

Mokkink LB, Prinsen CAC, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB. The COnsensus-based standards for the option of health measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement musical instrument. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(2):105–13. doi:x.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0143.

-

de Vet HCW, Knol DL, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB. Measurement in medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

-

Roy JS, Macdermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:623–32.

-

Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure out: the Dash (disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and caput). Am J Ind Med. 1996;29:602–viii.

-

Finsen V. Norwegian version of the Nuance questionnaire for exam of the arm shoulders and manus. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2008;128:1070.

-

Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Wright JG, Tarasuk Five, Bombardier C. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and mitt outcome measure in dissimilar regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;xiv:128–46.

-

Angst F. The new COSMIN guidelines face up traditional concepts of responsiveness. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;fourteen:152.

-

Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:102–nine.

-

Walker-Os KE, Palmer KT, Reading I, Cooper C. Criteria for assessing pain and Nonarticular soft-tissue rheumatic disorders of the neck and upper limb. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;33:168–84.

-

Solway S, Beaton DE, McConnell Southward, Bombardier C: The DASH upshot mensurate User's transmission: disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand. Inst. For work & wellness; 2002.

-

Haldorsen B, Svege I, Roe Y, Bergland A. Reliability and validity of the Norwegian version of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:78.

-

Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y: Evolution of a shoulder pain and inability index. Volume 4; 1991.

-

Bot SDM, Terwee CB, van der Windt DAWM, Bouter LM, Dekker J, de Vet HCW. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:335–41.

-

Colina CL, Lester Due south, Taylor AW, Shanahan ME, Gill TK. Factor structure and validity of the shoulder pain and disability index in a population-based written report of people with shoulder symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:8.

-

Desai AS, Dramis A, Hearnden AJ. Critical appraisal of subjective outcome measures used in assessment of shoulder disability. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:9–13.

-

Ekeberg OM, Bautz-Holter E, Tveitå EK, Keller A, Juel NG, Brox JI. Agreement, reliability and validity in 3 shoulder questionnaires in patients with rotator gage illness. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;ix:68.

-

Largacha M, Parsons IM, Campbell B, Titelman RM, Smith KL, Matsen F. Deficits in shoulder function and general health associated with xvi common shoulder diagnoses: a report of 2674 patients. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2006;15:30–9.

-

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B: SF-36 health Survey transmission and interpretation guide. 1993.

-

Loge JH, Kaasa S, Hjermstad MJ, Kvien TK. Translation and performance of the Norwegian SF-36 health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. I. Information quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1069–76.

-

Mintken PE, Glynn P, Cleland JA. Psychometric properties of the shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and paw questionnaire (QuickDASH) and numeric pain rating scale in patients with shoulder pain. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2009;18:920–6.

-

Michener LA, Snyder AR, Leggin BG. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating calibration in patients with shoulder pain and the effect of surgical status. J Sport Rehabil. 2011;xx:115–28.

-

Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for pattern. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17:163–lxx.

-

Kamper SJ, Ostelo RWJG, Knol DL, Maher CG, de Vet HCW, Hancock MJ. Global perceived effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, only ratings are strongly influenced by electric current status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:760–6.

-

Guyatt GH, Norman GR, Juniper EF, Griffith LE. A critical look at transition ratings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:900–viii.

-

Schmitt J, Di Fabio RP. The validity of prospective and retrospective global change benchmark measures. Curvation Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:2270–half dozen.

-

Munro BH. Statistical methods for health intendance research. fifth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

-

de Boer MR, Moll Air-conditioning, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Völker-Dieben HJM, van Rens GHMB. Psychometric properties of vision-related quality of life questionnaires: a systematic review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:257–73.

-

Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–40.

-

van Kampen DA, Willems WJJ, van Beers LWAH, Castelein RM, Scholtes VAB, Terwee CB. Determination and comparison of the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC) of four-shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). J Orthop Surg Res. 2013;eight:40.

-

de Vet HCW, Ostelo RWJG, Terwee CB, van der Roer Northward, Knol DL, Beckerman H, et al. Minimally important alter determined by a visual method integrating an anchor-based and a distribution-based approach. Qual Life Res. 2006;16:131–42.

-

Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K. Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:207–21.

-

Schuller W, Ostelo RWJG, Janssen R, de Vet HCW. The influence of study population and definition of improvement on the smallest detectable modify and the minimal important change of the cervix disability index. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:53.

-

De Vet HCW, Foumani M, Scholten MA, Jacobs WCH, Stiggelbout AM, Knol DL, et al. Minimally of import alter values of a measurement instrument depend more than on baseline values than on the type of intervention. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:518–24.

-

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–49.

-

Lundquist CB, Døssing 1000, Christiansen DH. Responsiveness of a Danish version of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and manus (DASH) questionnaire. Dan Med J. 2014;61:A4813.

-

Michener LA, Snyder Valier AR, McClure Prisoner of war. Defining substantial clinical do good for patient-rated outcome tools for shoulder impingement syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:725–30.

-

Franchignoni F, Vercelli Southward, Giordano A, Sartorio F, Bravini E, Ferriero G. Minimal clinically of import difference of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure (Nuance) and its shortened version (QuickDASH). J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44:30–9.

-

Lehman LA, Sindhu BS, Shechtman O, Romero Southward, Velozo CA. A comparison of the ability of two upper extremity assessments to measure out change in function. J Hand Ther. 2010;23:31–40.

-

Offenbächer M, Ewert T, Sangha O, Stucki 1000. Validation of a German version of the "disabilities of arm, shoulder and hand" questionnaire (DASH-G). Z Rheumatol. 2003;62:168–77.

-

Fayad F, Lefevre-Colau MM, Mace Y, Gautheron V, Fermanian J, Roren A, et al. Responsiveness of the French version of the disability of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (F-Dash) in patients with orthopaedic and medical shoulder disorders. Jt Bone Spine. 2008;75:579–84.

-

Terwee CB, Roorda LD, Dekker J, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Peat G, Jordan KP, et al. Heed the MIC: large variation among populations and methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:524–34.

-

Beaton DE, Van Eerd D, Smith P, Van Der Velde G, Cullen Thousand, Kennedy CA, et al. Minimal change is sensitive, less specific to recovery: a diagnostic testing approach to interpretability. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:487–96.

-

Schmitt JS, Di Fabio RP. Reliable alter and minimum of import divergence (MID) proportions facilitated grouping responsiveness comparisons using individual threshold criteria. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1008–18.

-

Gummesson C, Atroshi I, Ekdahl C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (Nuance) outcome questionnaire: longitudinal construct validity and measuring cocky-rated health change afterwards surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:eleven.

-

Schmitt J, Abbott JH. Global ratings of change practise not accurately reverberate functional change over fourth dimension in clinical do. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45:106–xi.

-

de Vet HCW, Terluin B, Knol DL, Roorda LD, Mokkink LB, Ostelo RWJG, et al. Three ways to quantify uncertainty in individually practical "minimally important change" values. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:37–45.

-

Raven EEJ, Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Van Montfoort DO, Pöll RG, Blankevoort 50, et al. Construct validity and reliability of the disability of arm, shoulder and manus questionnaire for upper extremity complaints in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2334–8.

-

Ebersole GC, Davidge K, Damiano M, Mackinnon SE. Validity and responsiveness of the DASH questionnaire as an outcome measure following ulnar nervus transposition for cubital tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:81e–90e.

-

Angst F, Pap Thou, Mannion AF, Herren DB, Aeschlimann A, Schwyzer HK, et al. Comprehensive assessment of clinical outcome and quality of life afterwards full shoulder arthroplasty: usefulness and validity of subjective outcome measures. Arthritis Care Res. 2004;51:819–28.

-

Angst F, Schwyzer H-K, Aeschlimann A, Simmen BR, Goldhahn J. Measures of adult shoulder office: disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire (Dash) and its short version (QuickDASH), shoulder pain and inability index (SPADI), American shoulder and elbow surgeons (ASES) society standardized shoulder. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(Suppl i):S174–88.

-

Macdermid JC, Khadilkar Fifty, Birmingham TB, Athwal GS. Validity of the QuickDASH in patients with shoulder-related disorders undergoing surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45:25–36.

-

Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, Meskers C, Naber R, de Ruiter T, et al. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome. Acta Orthop. 2014;85:314–22.

Acknowledgements

We would like to give thanks all the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Norwegian Fund for Post-Graduate Training in Physiotherapy (Grant numbers 76,326, 2015).

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be share due to personal data protection.

Authors' contributions

TR carried out the design of the study, conducted data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. BH and IS gathered information. YR, BH, IS and LIS revised the manuscript critically. LIS supervised the project. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approving and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol was canonical by the Regional committees for medical and health research ethics (REC Due south East), and was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Date: 5th June 2008 ID: 163-08086d 1.2008.131.

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/goose egg/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Rysstad, T., Røe, Y., Haldorsen, B. et al. Responsiveness and minimal important change of the Norwegian version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (Nuance) in patients with subacromial pain syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18, 248 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1616-z

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12891-017-1616-z

Keywords

- Dash

- Responsiveness

- Minimal important change

- MIC

- Cosmin

- Concrete therapy

Source: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-017-1616-z

0 Response to "Disabilities of Arm Shoulder and Hand (Dash) Review"

إرسال تعليق